Slow Streets Pave the Way to Better Bike Cities

By: Kiran Herbert, PeopleForBikes' content manager

Time and again, we’ve seen that when speed limits fall, safety rises — as do cities’ Bicycle Network Analysis scores.

“Slow streets are safe streets.” While somewhat cliche, that oft-repeated adage is also true: Speed is a key factor in traffic deaths. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, speed played a role in a quarter of all fatal crashes in 2018 — as speed limits and speeds increase, so do fatalities. Between 2019 and 2021, as speeding has increased, per capita vehicle deaths have only gotten worse, rising an astonishing 17.5%.

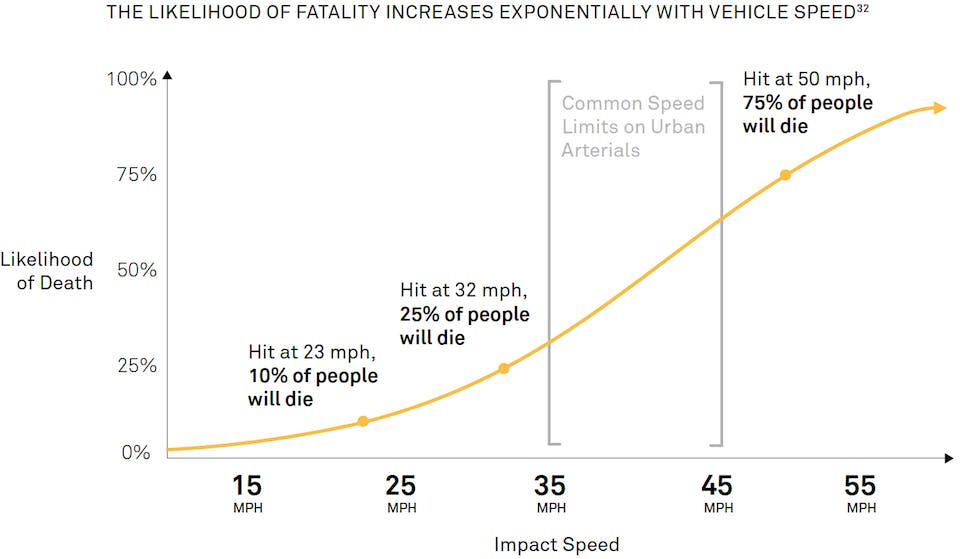

All of this is terrible news for pedestrians as well as bicyclists, who make up a fifth of traffic deaths and are far more vulnerable to dangerous street design and aggressive driving. As the National Organization of Transportation Officials (NACTO) notes, vehicle speed at the time of impact is directly correlated to whether a person will live or die. That means that a car traveling at 35 mph is five times more likely to hit and kill a person than a car traveling at 20 mph. Not to mention, cars traveling at higher speeds are also more likely to crash in general.

Because the likelihood of fatality increases exponentially with vehicle speed, even small reductions in speed limits can have an outsized effect. The Highway Safety Manual shows that deadly crashes can be decreased by 17% if speeds are reduced by just 1 mph, while a separate study from Sweden's Lund Institute of Technology found that a 10% reduction in the average speed led to 34% fewer fatal crashes.

Not only can lower speed limits save lives but they also make it easier for people to choose not to drive. When travel speeds are low, bikes and cars can safely mix. When cities reduce speed limits on residential streets to 25 mph or lower, their Bicycle Network Analysis score — a major component of the PeopleForBikes' City Ratings system — improves. Speed limit reductions on other kinds of streets can also improve BNA scores. In fact, the fastest way for cities to make streets safer for bicycling, and thus improve their scores, is by slowing down streets.

Aside from better, more accurate data inputs, the main reason cities experienced a drastic improvement in their 2022 City Ratings score was due to speed limit reductions. In Miami, after the city lowered speed limits from 30 to 25 mph on neighborhood streets, its BNA score jumped from 4 to 20. As a result, Miami’s City Ratings score went from 13 in 2021 to 26 in 2022. Similarly, in 2021, when Knoxville, Tennessee, decided to lower its default speed limit from 30 mph to 25 mph, its BNA score improved from 8 in 2021 to 24 in 2022 and its City Ratings score jumped from 19 to 31. Seattle’s BNA score also rose from 53 to 58 last year, thanks in part to the city’s widespread reduction of speed limits on most major roads.

From 2020 to 2021, St. Paul, Minnesota's City Ratings score also increased significantly, owing to a series of infrastructure improvements but also to the city lowering its default speed limits, switching from 30 to 20 mph on residential streets and 25 mph downtown. St. Paul made the decision after the Minnesota state legislature changed its laws in 2019, allowing cities to deviate from the state standard and set speed limits on their own streets for the first time. While not required to repost new signage on every single residential street (the city instead relied on a substantial marketing campaign), St. Paul still installed or changed more than 725 speed limit signs on city-owned streets.

Alongside concerns about enforcing new speed limits, the cost and labor required to repost street signs can be a major deterrent for cities looking to rethink speed limits. In Texas, cities aren’t allowed to change the default speed limit — 30 mph on residential streets — unless it also posts new signage on every affected street. If the state’s largest city, Houston, wanted to change its default speed limit, the estimated cost of posting new signs citywide would be about $25.6 million. In 2020, the capital city of Austin voted to reduce the speed limits on particular roads by 5 to 10 mph, lowering the default residential speed limits down to 25 mph. Due to the signage requirements, however, the process has been slow and expensive — many neighborhoods remain unchanged and under state law, police can't enforce the lower speed limits until signs are posted.

In Flower Mound, Texas, a city of some 80,000 people just north of the Dallas-Fort Worth Metropolitan Area, the town has gradually been reducing speed limits since 2019. According to Matt Hotelling, senior engineering transportation manager with the Town of Flower Mound, the process started with school districts before expanding so that neighborhoods could petition the town to lower speed limits.

“If the neighborhood had overwhelming support, we’d take it through our city’s transportation commission, and then if they provided a favorable recommendation — which 99% of the time they did — it would go on to council for a vote,” said Hotelling. “And again, almost 99% of the time, they decided to lower speed limits.”

In 2021, by the time Flower Mound’s transportation commission opted to look into a town-wide policy for speed limits, close to one-fifth of the town’s streets had already been changed. After weighing the numerous safety benefits, the commission eventually recommended that all residential streets should default to 25 mph — if a neighborhood wanted a 30 mph minimum, the onus would now be on them to go through the process of changing it back. In the end, four out of five council members voted to lower the default speed limit.

Hotelling notes that the change wasn’t contentious. After all, much of Flower Mound’s streets have already been changed to 25 mph and the safety benefits are well-known and accepted. Flower Mound’s BNA Score improved four points as a result of the residential speed limit reduction.

Again, what’s proved most difficult is Texas’ posting requirement. Some neighborhoods have resisted signs, especially when their streets are small and going fast is already near impossible. Some signs can be posted at every entrance to a subdivision to a thoroughfare, which raises the question of whether or not Flower Mound can just post signs at its corporate limits.

“That’s part of what we’re going through now, checking with the local [Texas Department of Transportation] TxDot folks,” said Hotelling. “I’m not sure if we’re going to get the green light.”

Although there have been some efforts at the state level to lower default speed limits, little progress has been made. In California, Assembly Bill 43 took effect this year, offering cities more control over their speed limits. Before the new law, the City of Los Angeles was actually required to increase speeds on many city streets. In March 2022, after the bill was pushed through, the L.A. Department of Transportation announced it was reducing speeds by 5 mph on more than 177 miles of city streets.

L.A. worked with its City Council to implement the new changes quickly and there’s hope that more places will follow suit, prioritizing roads with high concentrations of vulnerable road users. There’s increasing evidence that when cities lower speed limits, it saves lives and encourages the sharing of our roadways. A widely celebrated success story comes from Spain: When the speed limit on single-lane urban roads was lowered to 18.5 mph, road deaths fell by 14%. In regard to cyclists, deaths were cut almost in half.

While an important start, lowering speed limits alone isn’t enough. Along with speed limit reductions, PeopleForBikes encourages cities to implement traffic calming features that ensure drivers follow the posted speed limit, as well as comprehensive bike networks for all ages and abilities. After all, people can and do disobey speed limits. Good design and widespread infrastructure, however, are powerful tools that can’t be ignored. Ultimately, both reductions in speed and traffic calming designs are necessary to create safer, bike-friendly cities.

Related Topics: