New Orleans' Bicycle Equity Index

By: Kiran Herbert, PeopleForBikes' local programs writer

In 2019, the Crescent City joined forces with Toole Design to let equity lead in the planning of its bike network.

Many cities have taken to using the term “equity” when describing transportation priorities and “equitable” when referring to the types of transit systems or bike networks they hope to create.

“The problem with that is that you have to define ‘equity’ and what it means in each community,” said Jennifer Ruley, mobility and safety lead engineer with the City of New Orleans. “We had to figure out how to define it for the purposes of planning out our bike network, particularly around access and safety and all the reasons people either choose to use a bike or have to use one.”

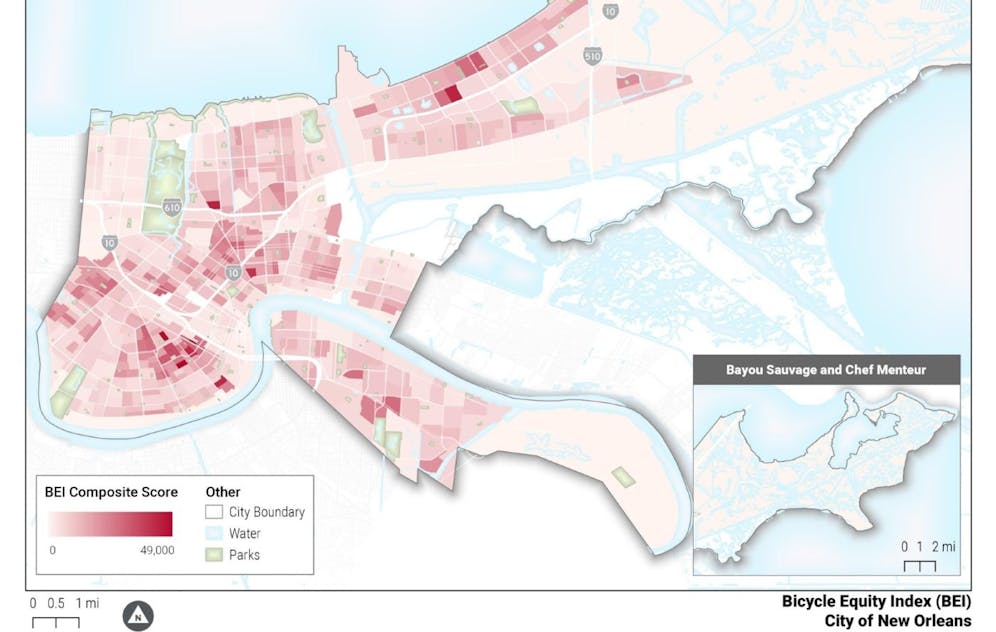

While researching, Ruley stumbled upon the League of American Bicyclists’ Bicycle Equity Index (BEI), a 2015 framework that attempted to measure equity in a city’s bike network using U.S. Census American Community Survey data. Compiled by Rachel Prelog, at the time an urban planning student at Texas A&M University, the BEI relies on five demographic indicators: transit dependency (those without access to a household vehicle), children under the age of 18, adults 65 and older, race/ethnicity and income below the federal poverty level. The BEI then determines where residents with those demographic characteristics live relative to the location of existing bike infrastructure. In this context, equity was determined by who has infrastructure near where they live and who does not.

At the end of 2019, Toole Design was brought in to collaborate with New Orleans on its bike plan, helping with all facets of the process, from the initial network analysis to the design of low-stress, separated bike lanes. Included in its scope of work was an equity analysis, which ultimately became one of the guiding principles of the plan alongside such factors as whether or not potential routes addressed connectivity, were useful or could be built in a timely manner. Using the League’s BEI as a starting point, New Orleans was keen on creating its own index.

“The conversation evolved to how we wanted to prioritize the different components of the analysis — whether we wanted them to be equally weighted or not — and what that might look like for New Orleans,” said Ruley. “We identified six or seven different hotspots or areas where the equity analysis was really pointing towards as priorities for bike network connectivity.”

Toole began working with city staff to draft a network plan that would help connect these hotspots to the proposed bike network. Ultimately, the firm identified more than 550 miles that would need to be built or upgraded, including 285 miles of protected bike lanes. New Orleans had already committed to building out 75 miles within a two-year timeframe, so the challenge then became prioritizing 75 miles of projects within that network that made meaningful connections from the get-go and could be implemented quickly.

To identify priority projects, Toole adjusted the original BEI’s methodology to more heavily weigh the needs of people who experience compound disadvantages that reduce access to transportation.

“When we have somebody without a car, that’s under 18, that’s a person of color and living below 80% of the median household income — they have several of these factors that increase their potential reliance on transit, walking or biking,” said Toole Project Manager Adam Wood. “We wanted to see those areas of extreme [need] and have that factor in some way.”

Ruley hoped to also identify communities overburdened with chronic diseases, but having previously worked for a public health nonprofit, she recognized the struggle to accurately obtain good data at a sub-neighborhood level. Since race and socioeconomic status are known indicators of things like hypertension, heart disease, obesity and respiratory issues, the BEI got the city closer to identifying an array of concerns without having all the data available.

“Health data was important to us so that we weren’t just focusing on transportation but biking as a tool for fitness and health,” said Ruley, adding that when COVID-19 hit, many of the hotspot communities saw more deaths. “It just reiterated the need to think about what we do using a bigger picture.”

After running its revised BEI, the city began a community engagement campaign, letting people know that it was using data to guide its decisions. By reaching out to nonprofits and community groups, the city worked to cultivate partnerships with local advocacy organizations and build trust, operating transparently and incorporating feedback.

“Building those relationships was crucial to getting more people involved,” said Ruley. “It paid off in ways we didn’t expect, such as converting a number of people and other organizations that didn’t directly align with bicycle improvements but they aligned in a different way, whether it was physical health or economic impacts.”

Although the city is behind schedule on the completion of its 75-mile network, largely due to complications presented by the pandemic and Hurricane Ida, it was able to complete the Algiers Protected Bike Lane Network. The Algiers neighborhood, one of the city’s oldest and the only one located on the West Bank of the Mississippi, had a high BEI score and was ripe for investment. The lane build-outs there are a shining example of what New Orleans set out to do: Engage the community around safe, connected bikeways that could be built fast in areas that needed them the most.

Learn more about the city’s accomplishments in Algiers in our Advocacy Academy video below:

While the city and Toole are happy with how the BEI turned out and New Orlean’s bike plan in general, Ruley and Wood see room for improvement. In our conversations, both noted the limitations of census data: It shows where people live, but it doesn’t show the routes they would take to access essential services, such as grocery stores, medical facilities or schools. In some cases, building a connection through a wealthy, white neighborhood might actually be the best option for increasing access for historically underserved neighborhoods.

“The data isn’t telling you where people go, need to go or would like to go,” said Ruley, touching on the fact that better data is needed alongside a comprehensive outreach strategy. “Part of the work is also figuring out a way to engage people around those issues.”

Higher quality transportation data — such as that generated through surveys, focus groups, polling or traffic data — is costly to obtain but would greatly benefit any index. Community meetings that touch on this information are biased towards those who show up or are invited to attend, so while important, they’re no stand-in for better data. Ideally, bicycle plans should incorporate both. In addition to procuring more detailed data related to people’s travel patterns, Ruley wishes she had been able to do more engagement, perhaps offering childcare or free food as incentives for folks to attend meetings.

Still, New Orleans remains a prime example of how data can be baked into a bicycle plan with the overall goal of creating more equitable outcomes. Both Ruley and Wood view the New Orleans BEI as a good first-case study and Toole continues to refine its approach to evaluating equity in other cities, including Austin, Texas. As another example, he points to Portland, Oregon’s Equity Matrix, which used census data in a similar fashion. One of Wood’s chief regrets, however, pertains to the way planners and policymakers tend to stop at measuring where people live, when truly analyzing equity requires measuring the outcomes that decisions have on peoples' lives.

“It’s problematic to throw the word ‘equity’ in — it implies putting a bike lane in a neighborhood will inherently increase equity when that’s not really true,” said Wood. “I regret that we couldn't go further to truly measure the equity of current conditions and of the [bike] plan's decisions, because we were limited in data, time and resources. As planners, we want repeatable processes for consistency, but they can overly simplify an incredibly complex challenge.”

In New Orleans, the BEI factored into infrastructure and planning decisions, which was an appropriate use and should be a baseline best practice for any city. For comprehensive guidance on incorporating equity throughout the planning process, Wood recommends referencing research — such as “Equity Analysis in Regional Transportation Planning Processes” or “Performance-Based Methodology for Evaluating Equity for Transportation System Users” — and adapting ready-made methodologies to the place and project resources.

The BEI’s limitations notwithstanding, all cities should use data to help guide actions with the intent of increasing equity. Not only is it a known method for removing bias in the planning process, but it will always be preferable to simply paying lip service without any structure or framework. What New Orleans recognized was that data must be coupled with inclusive engagement. Unless you’re involving the community you seek to serve in the planning process and humanizing your census data, equitable outcomes will remain out of reach.