Inclusion on Main Street

By: Kiran Herbert, local programs writer

A 1.5-mile stretch of Broad Street in Providence, Rhode Island, is slated for a holistic mobility upgrade and community engagement is an integral part of the plan.

In small towns and big cities across America, certain thoroughfares form the lifeblood of a place, serving as cultural and commercial hubs filled with restaurants, shops and places for the community to gather. Sometimes these streets define a particular neighborhood and other times they’re defined by a certain ethnic group or historic identity. In Providence, Rhode Island, Broad Street is such a place.

Clocking in at roughly 4 miles, Broad Street maintains an international character, known for its large Asian markets, popular Dominican restaurants, numerous bodegas and lively street life. Compared to Providence and Rhode Island as a whole, Broad Street is incredibly diverse, with a primarily Latinx demographic, as well as large Black and Asian populations. Roughly 40% of Broad Street’s inhabitants are foreign-born (primarily Caribbean and Central American) and almost 35% live in poverty (the national average hovers around 15%). Additionally, some 40% of Broad Street community residents commute via walking, biking or transit and 25% of households do not have access to a car, significantly higher than the statewide and national averages.

It’s these characteristics that, in 2017, inspired Mayor Jorge O. Elorza to rebrand Broad Street as Providence’s Latino Cultural Corridor, a move that accompanied $4.3 million in funding, the majority earmarked for bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure. The idea for developing Broad Street to become more bike and pedestrian-friendly really began in 2006, however, and in the 15 years since, has been pushed back and reimagined numerous times. The extended timeframe has provided ample opportunity for community engagement, and since 2019, the Providence Streets Coalition has taken on the bulk of that work.

“The project development timeline has just been so long,” said Liza Burkin, lead organizer of the Providence Streets Coalition, noting that the city did a demonstration day in 2018 and still hasn’t started work. “We really felt like we needed to remind people of the entire timeline of all the public processes that have gone on over the last 15 years to get us to this point, including the demonstration day and all the safety data.”

The Providence Streets Coalition formed in 2019 as the city’s first mobility advocacy organization, establishing itself at the intersection of environmental and social justice. In the last couple of years, the group has brought that spirit to Broad Street. The core of the coalition's messaging has been driven by crash data, which highlights Broad Street's abysmal safety record for both pedestrians and bicyclists: Between 2009 and 2015, Broad Street experienced the greatest number of crashes involving people walking or riding a bicycle out of any corridor in Providence.

“We just had another fatality this summer and we had one of the City Council members get into a car crash on Broad Street,” said Burkin. “It’s a real safety problem and every passing year people understand that more and more.”

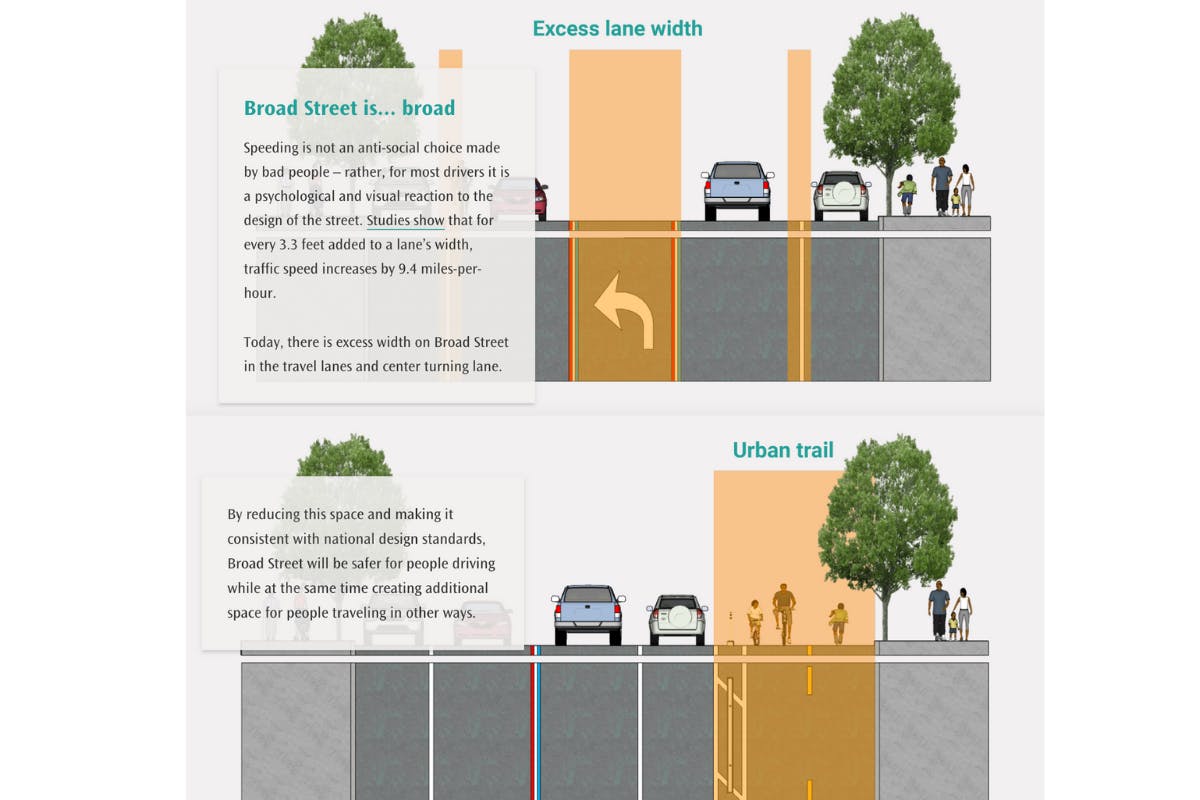

The coalition’s outreach also focuses on the fact that the city is positioning the Broad Street work as a holistic mobility project, as opposed to a bike lane project (although 3 miles of bike lanes are also part of the plan). Rather, the emphasis has been on the new crosswalks, traffic signals and bus islands, as well as the reconfiguration of everything in an integrated way, creating a balanced street for all users, drivers included. The current design even retains street parking on both sides of the road — based on feedback from residents and businesses — and instead will create bike lanes using space from a central turning lane, an unsafe and chaotic feature many folks are excited to get rid of.

A 600-person phone poll conducted by the Providence Streets Coalition in March of this year, with oversamples of Latinx voters and those under 40, highlighted residents' support for new bicycle infrastructure. Interviews conducted in English and Spanish showed that 63% of people believe Providence should have more protected bike lanes that are separated from driving lanes, even if it means reducing driving lanes and less on-street parking. Additionally, 70% indicated that they would like to ride a bicycle more often, particularly if infrastructure designed to improve bike safety were built throughout the city. When it came specifically to the work proposed for Broad Street, 87% of residents were in favor and many said that they would ride their bikes instead of driving (45%), or that they'd shop and dine more on Broad street (50%), if there were more safe and accessible options.

“We’re hoping to create a safe, beautiful street where the local businesses can really thrive,” said Burkin. “A street that attracts more people and gives them the ability to move quickly and easily.”

The bike lanes on Broad Street are part of a 75-mile network Providence is in the midst of building, offering greater connectivity for residents. Broad Street is an important thoroughfare and the new infrastructure will provide a crucial way for those on foot or bike to access its businesses, jobs, schools, community services and Roger Williams Park, the city’s largest greenspace.

“The park is flanked by highways and major streets and it's very difficult to get to via active modes if you don’t live right in the neighborhood,” said Burkin. “Connecting to Roger Williams Park is a big deal for the rest of the city and south Providence neighborhoods.”

The southside of Providence has been disinvested in for generations and the coalition consistently emphasizes the magnitude of the city’s investment in outreach, promoting safety first and foremost, but also how a revamped street will improve the neighborhood’s ability to flourish for decades to come. In order to celebrate the culture and history of the corridor, while sharing out the city’s plan, the Providence Streets Coalition created a virtual story map: “Broad Street Was, Is, And Will Be.”

Comprehensive and colorful, the website tracks the history of everything from Native American displacement to redlining, moving on to the diversity that defines Broad Street today, as well as the safety data and economic demographics of the area. Finally, the site reminds folks of the city’s proposed redesign and all of the community engagement work that’s already been done, including the 2018 3D demonstration day where residents provided feedback in real-time.

A section of the Providence Streets Coalition’s website on Broad Street.

Recognizing that the public’s memory can be short, the Providence Streets Coalition took advantage of the project’s two-year delay due to COVID-19 to create the story map and promote it alongside its standard forms of outreach, including door knocking along the corridor, conducting one-on-one meetings with business owners, and biking a mobile community engagement trailer multiple times a week to block parties, farmers markets and outside of the nonprofit Youth in Action’s headquarters.

“We’re using a combination of in-person and virtual outreach to complement one another as the project nears construction,” said Burkin. “The website is the one cohesive place where people can access it all and we’re trying to get it out to as many people as possible.”

The coalition vetted the website with many of its community partners before launch, ensuring that the content was clear and the Spanish translation was as good as possible for the variety of ethnicities in the area. In addition to a coordinated email campaign and handing out postcards with QR codes at events such as the Dominican Parade, the coalition is preparing a texting campaign targeting 5,000 Broad Street residents and business owners. In addition to the website URL, the texts will contain information about the final community meeting, set to take place in the coming month. Although the project is currently out to bid and set to break ground as soon as October, the continuing COVID-19 pandemic and its Delta variant remain an ever-present variable.

Until construction is underway, the Providence Streets Coalition will continue its outreach efforts, canvassing the street and working in conjunction with organizations such as the Southside Cultural Center of Rhode Island and Community Angels. Although Burkin is optimistic about the engagement work that’s been done, she’s reluctant to be too congratulatory, noting that, “It won’t be a proven success for many more months — if not years.” After all, there are plenty of languages spoken outside of Spanish or English on Broad Street, including a variety of South Asian and West African languages, as well as Haitian Creole. For everyone that’s been engaged and included so far, there’s a neighbor that has not. As with all things community engagement, the work is ongoing and never done.