How to Build a Bike City: Lessons from CDMX

By: Kiran Herbert, PeopleForBikes’ content manager

In the last four years, bicycling in Mexico City has transformed thanks to a connected network, dedicated infrastructure, and an emphasis on equitable mobility.

When we talk about the great bike cities, we often look to Europe, and rightfully so — there are few places that can compare to the sheer scale and quality of bicycling in a place like Copenhagen, Sevilla, or, more recently, Paris. It’d be a mistake, however, to not consider Latin America, where places like Bogota and Mexico City have become leaders on the sustainable transportation front — and notably, have done so with substantially smaller budgets.

Mexico City has been a leader in bicycling since 2007 when it first launched its Muevete en Bici open streets program, which every Sunday, bans car traffic along seven city streets including Paseo de la Reforma, a wide avenue that runs diagonally across the heart of the city. The closure, which is more than 30 miles long and traverses six districts, brings — at its height — some 90,000 people from all walks of life to the streets where they’re free to walk, roll, and ride in solidarity and without fear. Still, it’s only in the last few years that the city has truly become a great place for people to bike every day of the week.

“In the last 20 years, things went really slow because it was more or less like experiments — there wasn’t a complete picture of what kind of infrastructure [the previous administration] wanted,” says Salvador Medina Ramírez, the general director of planning and policies at Mexico City’s Ministry of Mobility. “There was a lot of bike infrastructure but it was not a network.”

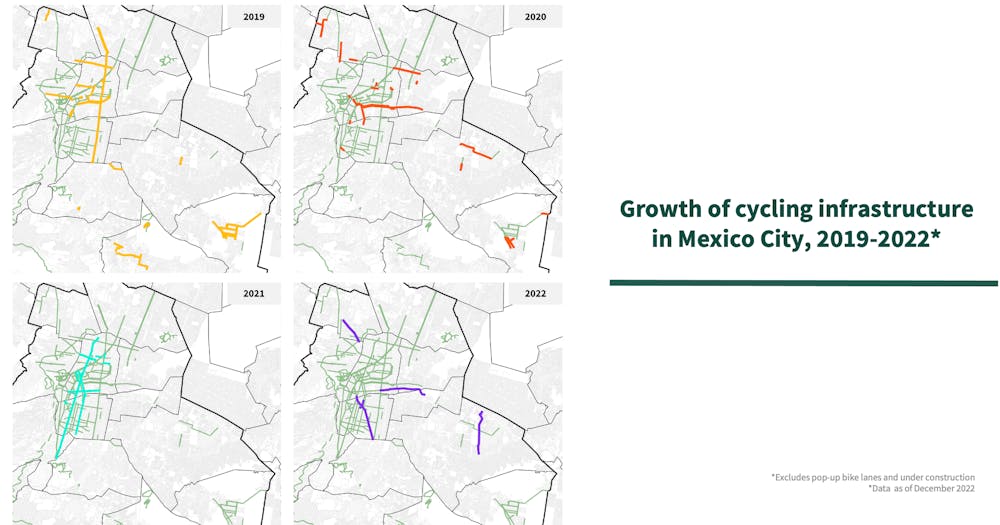

Since 2019, when Ramírez started, the bike network has begun to ramp up, a change he attributes to a combination of political will, a faster build pace, and a more holistic vision for a connected bike network — one that’s truly integrated with the city’s existing transit infrastructure. Mexico City’s current head of government, Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo, is committed to improving mobility in the city, and crucially, she sees bicycling as an essential mode of transportation. With official backing and funding, planners were able to move quickly to get more than 140 miles of new bike infrastructure on the ground between 2019 to 2022.

Photo credit: Mexico City’s Ministry of Mobility

When determining where to build, metro connections were prioritized and bike hubs were built alongside lane miles, ensuring people could travel by bike across one of the world’s largest metropolitan areas.

“If you try to make all the trips by bike door to door, it would be impossible,” says Ramírez. “The integration with public transport is essential if you want to make people use the bike. If you don’t, they will change to other modes like cars or motorcycles.”

Today, being multi-modal in Mexico City has never been easier, with bike lanes connecting to the metro but also bus lines and the elevated trolley, alongside public parks and schools. Crucial to building those key connections is ensuring there is ample, secure bike parking — places with security cameras where you can register and leave your bike without fear of it getting stolen or picked over for parts. In total, there are 10 bike parking facilities throughout Mexico City, mainly near stations that are around the city center, with capacity for anywhere from 80 to 400 bikes.

At the end of many metro lines within Mexico City’s center, riders can once again bike, this time using bike share. Mexico City was an early adopter of shared micromobility — the EcoBici system first launched in 2010 and while it had a slow start, today it’s the largest in Latin America. Over the next few months, EcoBici will grow from 480 to 687 stations, and from 6,500 bicycles to 9,300. While the system doesn’t include any e-bikes (the financials of expansion didn’t allow for them), Mexico City is relatively flat.

Until recently, EcoBici was government-owned, meaning the city was responsible for buying all the bikes and stations. While the model ensured that bike share was operated for the public benefit, it was costly. In 2021, Mexico City made the decision to solicit private investment in order to expand its Ecobici system. Looking to other cities for inspiration, including Barcelona, Argentina, and London, officials decided to sign on with Lyft to provide its assets and to seek sponsorships, all while ensuring bike share remained a government enterprise.

“This is public transportation operated by a private company,” says Guillermo Ávila, Mexico City’s director of road security and sustainable urban mobility systems. “It needs to work as we believe it should work.”

For Silva and others working on bicycling in Mexico City, bike share is essentially an extension of its transit system and is treated accordingly. Case in point: Since 2013, Ecobici has been fully integrated into the TCDMX integrated mobility card, which is used for access to the Metro, trains, and buses in addition to bike share. While EcoBici doesn’t currently have a low-income program, an annual membership includes unlimited 45-minute rides for less than $28 a year. There are also plans to launch a more affordable membership program for students and older adults, as well as a cash payment system (for those unable to pay, there are also free bikes available to rent for up to three hours at a time via Bicigratis stands throughout the city).

Ecobici, Mexico City's bike share system, is the largest in Latin America and continuously expanding.

Naturally, the city’s bike share system has grown alongside Mexico City’s network of bike lanes. The city is now focused on connecting places on its outskirts to complement the existing network, targeting poorer neighborhoods where bicycling is already the mode of choice.

“In the last few years, infrastructure has been spreading to parts of the city that needed the infrastructure most,” says Ireri Brumón Martínez, deputy director of cycling systems at Mexico City’s Ministry of Mobility. “Some districts already used bicycles but they didn’t have cyclist infrastructure, so the investments are going towards those parts of the city outside the center.”

To build out its network, Mexico City isn’t relying on just one type of infrastructure but has instead incorporated a variety of solutions, always accounting for local necessities. This strategy not only makes sense from a cost-benefit perspective but it’s also more equitable. Complementing its network expansion are government-backed programs that teach children and adults how to ride a bicycle, as well as separate courses for learning to use a bike for transportation.

Other programs for increasing access and building a culture of bicycling are often run by Mexico City’s bike advocates, a group of passionate cyclists behind many of the reforms playing out today. Chief amongst them is Areli Carreón, Mexico City’s designated Bike Mayor and one of the founders of Bicitekas, an organization that promotes the use of bicycles locally and lobbies for policy change.

“We have managed to have many truthful, awesome achievements during the past years,” says Carreón. “In 2020, we managed to change the constitution to include the right of safe and equitable transportation.”

Mexico’s “Right to Mobility” amendment is distinct in that it specifically details safe mobility as a human right, and Carreón sees the potential for it to forever change budget and policy decisions in Mexico City and the rest of the country. Having safe mobility enshrined as a constitutional right will help in holding folks accountable and setting the precedent for safe infrastructure that works for people of all ages and abilities, no matter their mode of choice.

While the amendment was in the works before the pandemic struck, it was the lockdowns of 2020 that created the biggest opportunity for cycling in Mexico City. In May of 2020, Bicitekas pushed for the creation of a huge pop-up bike lane on one of the capital’s longest thoroughfares, Avenida de los Insurgentes. Made from recycled materials and erected in just three days, the 28-kilometer, two-way cycle lane resulted in an increase of bicyclists of up to 275%. Its success led to the creation of a permanent, high-quality bike lane on the avenue, a huge win for mobility in the city.

“Pop-up bike lanes installed during the pandemic were really well accepted,” says Ramírez. “It made it possible to put a bike lane, and if it was well-planned, it would be socially accepted without much problem.”

Adding to the shift in infrastructure and cultural perceptions that occurred during the pandemic were all the new riders that found cycling. In Mexico City, bike shops were named an essential service in 2020, allowing the sale of bikes to continue and helping usher in people that might not have started bicycling otherwise.

“One of the things that changed with the pandemic was people started to appreciate more and more doing activities in the street,” says Ramírez. “In most of Mexico, [biking] is really common but with the middle class, it was not so common, so that changed a lot.”

Today, everyone agrees that there’s still work to be done. Like many places around the world, wealthier, more tourist-focused areas still have better bike infrastructure and Mexico’s City’s network is far from complete. As in cities across the world, more safe, high-quality infrastructure and increased road safety are needed to bring more people to bicycling. Carreón cites a local study showing that a significant number of people would be willing to ride if those two things were addressed. To get there, however, she sees political will and engaging the private sector as a must.

“The private sector has just as much of a stake in the game,” says Carreón, speaking specifically of those that sell bikes and services. “They should take a step forward to help this advocacy work because they’ll benefit from it.”

Mexico City has a population of more than 8.8 million people — if just a small fraction took up bicycling (a great option in a place notorious for bad traffic and poor air quality), the transformation and impact on the bike industry would be tremendous. Even without private sector investment, Mexico City has made incredible progress toward becoming a great place for cycling. With a City Ratings score of 57, it’s a step above most places in the U.S. and constantly improving, thanks to a combination of political willpower, a focus on building a connected network and constructing high-quality infrastructure fast, integrating bicycling with transit, and investing public funds in bike share and other equity initiatives.

“In Mexico City, we took into account three main things,” says Martínez, naming the government’s focus on infrastructure, access through bike share and transit, and culture, by way of the city’s open streets events and educational opportunities. “Those three things, they have to be connected. You have to do it all.”

Related Topics: