What Makes a Good Electric Bike Incentive Program?

By: Kiran Herbert, PeopleForBikes' local programs writer

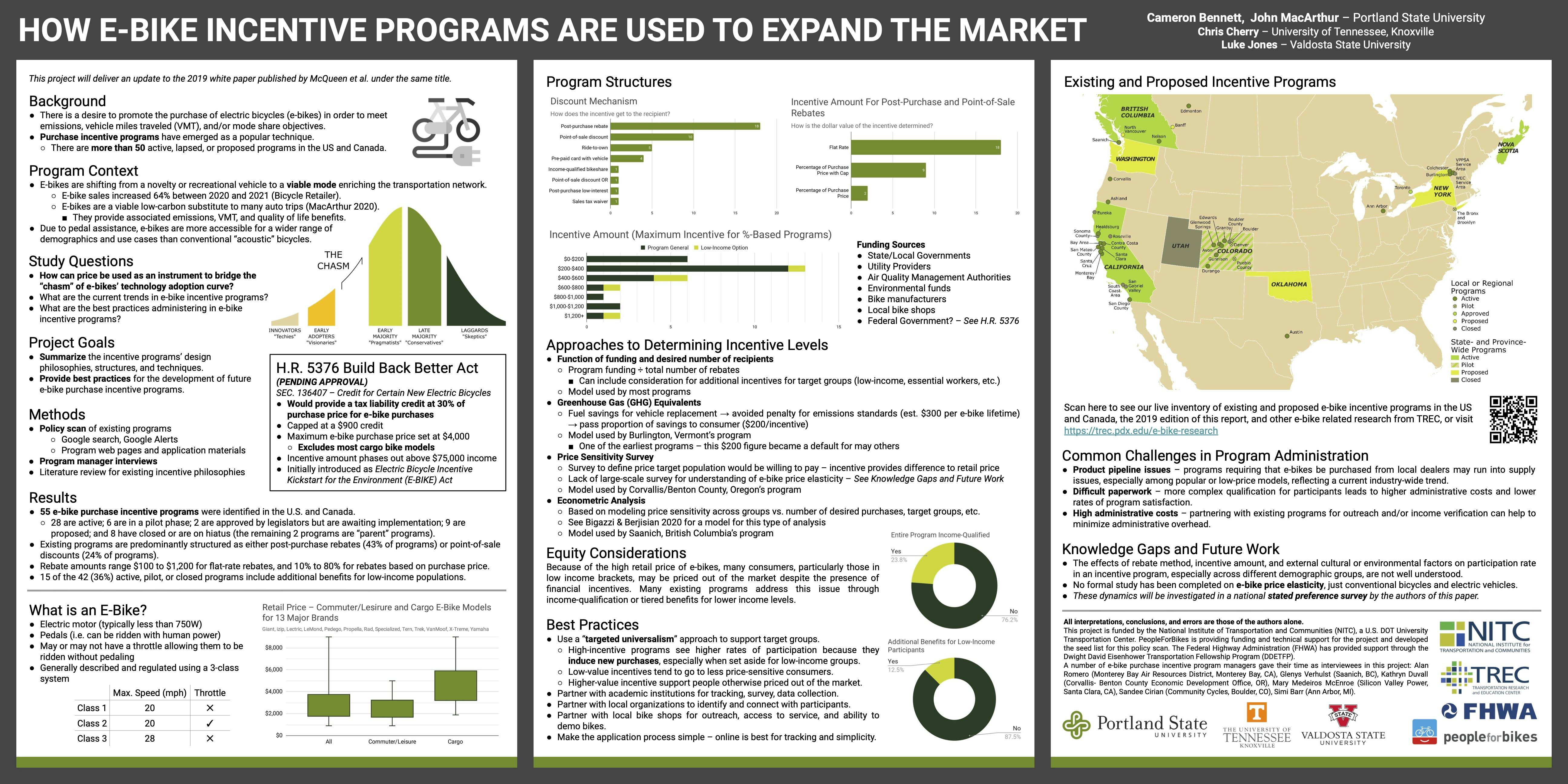

Researchers created a table tracking every e-bike incentive program in North America, providing a point of reference for new policies and future research.

Electric bicycles are all the rage. Not only are they outselling all-electric cars by about two-to-one, they’re also a favorite solution of urbanists looking to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, increase mobility options for underserved populations and transform our car-centric cities. E-bikes help people bike further for longer, typically serving as a car replacement and opening up bicycling to older populations and differently-abled riders. The main barrier to more widespread adoption, however, is cost: Most e-bikes typically run anywhere from $1,000 to upwards of $5,000 for some higher-end models and cargo bikes.

While the federal government currently offers a federal tax credit for electric cars of up to $7,500, nothing similar exists for people buying an electric bike. The Build Back Better Act does include a federal tax credit for e-bike purchases, and while it remains a priority for this administration, the bill has stalled in Congress. With a lack of government initiative, more and more states, counties and cities around the country are taking matters into their own hands, creating e-bike incentive programs that are as varied in substance as they are geographical.

For governments and advocates looking to encourage electric bicycle use, a new tool from Portland State University (PSU) researchers offers an overview of existing incentive programs in the U.S. and Canada. The E-Bike Incentive Programs in North America Table tracks purchase incentive programs and key details that can provide a point of reference for the development of future programs, policies and research, as well as inspire healthy competition amongst regions. To create it, a PeopleForBikes tracker of U.S. programs was expanded to include those in Canada. The final tool boasts some 60 different programs, some active, others expired or proposed.

John MacArthur, a researcher at PSU's Transportation Research and Education Center (TREC), led the development of the tool alongside PSU transportation engineering master's student Cameron Bennett.

“These programs are everywhere but there’s still not a lot of awareness of them,” said Bennett. “The majority fall in that $200-$500 range, although there are outliers on both ends.”

A program in Ann Arbor, Michigan, for example, offers every person who purchases an e-bike $100 off at the point of sale, while a program in Corvallis, Oregon, provides a $1,200 point-of-sale discount with an application. Many are climate-related, and thus secure funding from government initiatives meant to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“An electric bike incentive program that’s specifically for low-income and historically disadvantaged community members can be a great way for cities to work their way towards both DEI and climate goals,” said Ashley Seaward, PeopleForBikes’ deputy director of state and local policy. Seaward cites Colorado as a good example of a place where climate-related funding is being used to help underserved populations. “They’re basically piloting a bunch of different e-bike programs throughout the state and seeing what makes the most sense.”

California is also unique in that there are several regional programs geared towards low-income households. In the Bay Area, those who have a household income at or below 400% of the current Federal Poverty Level ($106,000 for a family of four) and live in a low-air-quality zone, can trade in an old car for a $7,500 prepaid PEX VISA. That money can then be used to either purchase an electric bike or for bike share. A program in British Columbia, Canada, run through the Clean BC Go Electric Transportation Options Program, similarly offers a voucher with vehicle trade-in, albeit for the drastically smaller amount of $845.

Banff, in Alberta, Canada, recently announced a program that includes a 30% rebate of up to $750 per residential household and a 20% rebate capped at $750 for businesses. There’s also a sliding scale for residents who are part of the low-income Banff Access program, which offers up to $1,000 off the purchase cost. Banff opted to cap the cost of an e-bike at $5,000 as part of the eligibility criteria, the intention being to limit high-end mountain and road bike purchases in favor of commuter models, as well as to offer priority to people who can’t afford an e-bike to begin with.

In Saanich, British Columbia, the municipal government already launched a program that offers a point-of-sale discount or a post-purchase rebate based on a custom scale with multiple incentive levels depending on income and household size. For example, for those who make above $43,000 a year, the rebate is $280, whereas income-qualified households making less than $33,000 receive $1,275. Tellingly, the lower-income tiers have already hit capacity whereas the third tier, which doesn’t require proof of income, is still available to residents.

“It’s also important to distribute incentives in an equitable way, across the spectrum of income,” said Bennett, noting that as with the American electric vehicle program, someone that can afford a Tesla doesn’t need a tax kickback. “The folks with the Saanich program have started calling this a Targeted Universalism approach — helping those that need it most is really important because it’s going to get people on e-bikes that otherwise wouldn’t.”

According to Bennett, the best programs work in tandem with trusted community partners — such as local housing authorities — who can take the lead on things like community engagement and income verification. The more administration that can be done online through a partner, with standardized forms that avoid hours of paperwork, the better. Just as we want to remove barriers to get more people on e-bikes, it’s important to design programs that are easy to use and run.

“One of the concerns we've heard from a lot of program managers is that, especially if you're doing an income-qualified program, it's a lot of work to manage them,” said Bennett. A program like the one in Ann Arbor, however, where everyone just gets $100 off at the till, is almost too easy. “You need a little bit of buy-in from the consumer and community,” says Bennett.

Electric bicycle incentive programs that provide prepaid debit cards or vouchers also make it easier for retailers, who can then simply run purchases as a sale, and consumers, who can shop normally and don’t have to put down money upfront. When the government agency acts as the sole provider and retailers don’t have to manage data, that’s considered a win, as is partnering with local bike shops, which helps build community, support the local economy and create a touchpoint for new riders needing guidance or repairs.

The issue with most of the programs currently out there, however, is that a $200-$500 incentive isn’t enough to convince someone to spend upwards of $1,000 on a new bike.

“The goal of these programs is to induce new purchases of e-bikes,” said Bennett. “If you’re already buying a bike, $200 sweetens the deal, but if you weren’t planning on buying an e-bike, it probably won’t change your mind. Higher incentive values change minds and help get more people on bikes.”

One of the first e-bike incentive programs was created in Burlington, Vermont, in 2018, where it was determined that for the power district, having people transition would save $200, so the city wanted to pass along that figure. That early program set a precedent that many have followed, for better or worse. The Corvallis program, which is administered by the City of Corvallis, landed on $1,200 after conducting a price sensitivity survey and asking the community what they want.

There is not currently enough data to say exactly what the secret recipe is — more follow-up surveys are needed to determine how programs were beneficial and who they served, along with research that helps us better understand the economic motivators that move people to purchase an e-bike. Bennett, MacArthur and Professor Chris Cherry, at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville’s Tickle College of Engineering, are using the tracker as a launchpad to study the latter.

We know that e-bikes are more efficient than traditional and electric cars and that they can have an exponential impact on greenhouse gas reductions if people use them to replace car trips. “The problem is, we don't really know how much of an incentive it takes to tilt someone's behavior,” said Cherry. “If I was going to buy an e-bike already, would giving me an incentive make me buy it sooner? And if I wasn't going to buy it — if I was going to buy a conventional commuter bike because I couldn't afford an e-bike — would an e-bike incentive make me buy an e-bike?”

The researchers will dive deeper into people’s habits using surveys, focus groups, and demographic data, looking at what amount of money it would take to affect someone’s interest in choosing a certain type of electric bike versus something else. The sample size will be geographically distributed and the researchers plan on asking questions around local bike infrastructure in order to ascertain other barriers to bicycling. They’ll also then examine how much greenhouse gas reduction that choice to purchase an e-bike would then result in, the goal being to be able to quantify emissions reductions based on certain e-bike purchases.

“Our approach basically is to ask about 1,000 or 1,500 people what are the attributes that we can quantify that are valuable to them,” said Cherry, adding that the ultimate goal is better incentive programs that account for what sways potential users and the impact getting them on an e-bike might have. “Some folks are seeing incentives as money off of a toy and not a tangible, real tool for transportation. We want to change that.”