Transforming Old Tires Into Bike Lane Barriers

By: Kiran Herbert, PeopleForBikes' content manager

In Memphis, a workforce development program is using old car parts to carve out space for bicycling.

In 2020, traffic fatalities in the Memphis area were up 50% compared to the year prior and they’ve only continued to climb, echoing national trends. To choose to bike or walk in such an environment can be dangerous and sometimes life-threatening, a fact not lost on the city’s transportation planners. What’s more, traffic fatalities and collisions aren’t the only car-related issues in Memphis: The city also happens to have a big problem with illegally dumped tires.

In early 2020, Laura Murray, a former Alta Planning + Design employee, had an idea to help tackle both issues at once. Murray found a local industrial artist, Tad Pierson, who’d been using tires as an art medium for more than a decade. The pair worked together on a novel concept — transforming old tires into new bike lane barriers — which they eventually pitched to the City of Memphis.

While the city was interested, it wasn’t able to fund a pilot and encouraged Murray and Pierson to find a nonprofit or community development corporation to collaborate with on a trial installation. They found both in the Binghampton Development Corporation (BDC), a nonprofit working to improve the quality of life in the Binghampton community, a historically disinvested neighborhood in central Memphis. In Binghampton, some 35% of residents live below the poverty level and the majority of folks identify as Black or people of color. The community also has a large immigrant population — 17 countries of origin exist amongst its 12,000 residents — and it’s common for new refugees to settle there.

The BDC has been active in the neighborhood since 2003 when it began pursuing a revitalization strategy through housing and economic development, as well as empowerment programs for those plagued by issues of systemic poverty. In addition to developing physical assets, like parks and neighborhood commercial services, and providing affordable rental and homeownership opportunities, the BDC invests in people through mentorship programs and hard- and soft-skill training for youth and adults.

Murray and Pierson’s timing was serendipitous. When they approached the BDC with their idea to build bike lane barriers using old tires, the organization was actively looking for warehouse-based opportunities for its job training program. As part of the roughly six-month-long, paid, full-time training and development program, BDC employees work on projects that range from mattress recycling to warehousing for trucking companies. After securing additional funding — some of which came from PeopleForBikes, alongside the Tennessee Department of Environmental Conservation, the Cummins Foundation, and the City of Memphis — BDC ran with the tire project.

“We had enough funding to pay for the equipment and our trainee’s labor for about 400 bike lane barriers made using the old tires,” said Andy Kizzee, director of the BDC’s business hub. “We manufactured in November and December [2021] and have been monitoring since.”

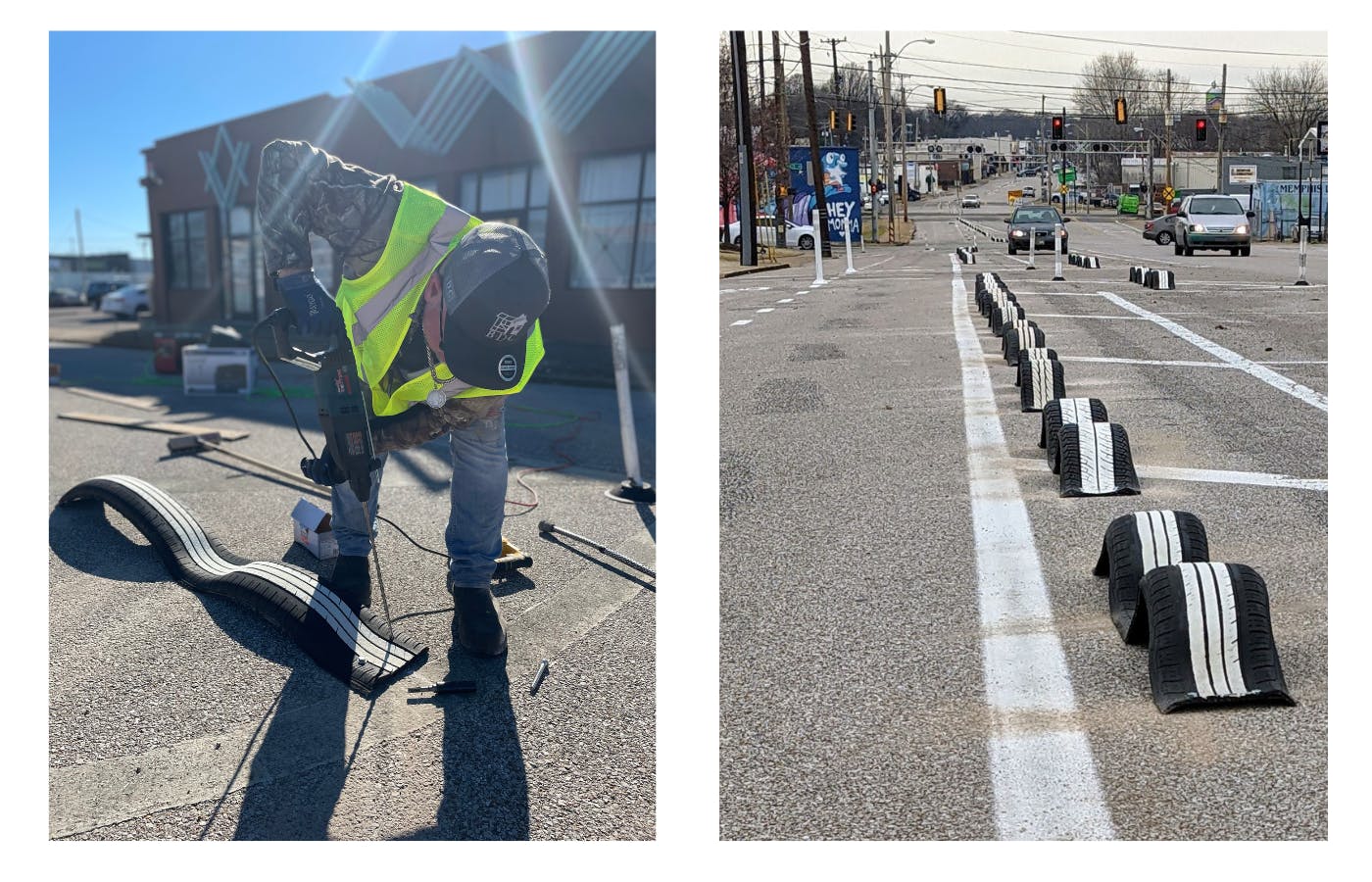

Employees working on the tire pilot have been involved in all stages of the process, from stripping down, shaping, and painting the tires to anchoring them to the road along a one-mile stretch of unprotected bike lane in Binghampton. Since installation, the tires have been monitored for traffic impacts, and different designs, paint methods, and anchoring techniques have been tested. Installation was completed in February 2022 and although the evaluation process will last a full year, so far less than 10 of the 400 barriers have detached from the roadway (those few that did were due to instances of extreme heat).

For Nicholas Oyler, bikeway and pedestrian program manager at the City of Memphis, the pilot has gone better than expected. The tire barriers are a low-cost alternative to flex posts, which are essentially plastic poles that delineate between a bike lane and traffic lanes. As almost any city planner can attest to, installing flex posts often results in lots of grievances from residents, mostly for aesthetic reasons. Oyler thought the tire barriers might elicit similar ire, but he’s been pleasantly surprised.

“I’ve received no negative complaints at all for any aspect of the tire barriers,” said Oyler. “I’ve actually received requests from people in other neighborhoods asking for the tires to be installed on their streets. What better measurement of success is there, in terms of a public reaction than people asking for them?”

While the tire barriers have held up well to impact, no one involved in the project would argue that a tire is actually going to stop a car. As with a flex post, if a driver is moving fast enough and makes a mistake, no low-cost barrier stands a chance.

“A concrete, raised median would be best — that would be true protection — but until we have funding to do that everywhere that’s needed, cities need a low-cost temporary alternative,” said Oyler. “Not only are the tire barriers locally sourced, but they have the added benefit of collecting discarded trash, reducing blight, and, through the workforce development program, providing an opportunity for people to improve their lives.”

The BDC job training program was specifically designed for people who fall into common “can’t work” or “won’t work” scenarios. This includes folks with a legal history and/or substance abuse issues, as well as people who have simply never worked before or lack the transportation options necessary to maintain a job. The BDC warehouse only employs local residents, and thanks to its central location in the Binghampton neighborhood, allows employees to commute by foot.

The tire project itself is particularly well-suited to the training program. First, the machine used to cut the tires is safe, a must for a learning environment with high turnover. The process of shaping, painting, and installing the tires also exposes trainees to a wide variety of different work tasks, which are both marketable and easy to learn.

“It’s perfect job training content,” said Kizzee, adding that the trainees have done a great job. “We’ve been pretty pleased with the product — it’s on par with the other commercially made [barrier] products.”

While Kizzee believes there’s still some room for improvement, other cities are already taking note. He recently presented the project alongside Oyler at this year’s Association of Pedestrian and Bicycle Professionals conference, resulting in a lot of exciting feedback from planners and city officials, especially those located in Sunbelt states (since the tire barriers are easily concealed by snow, they’re not well-suited to colder environments). Kizzee and the BDC are now exploring the possibility of selling the tire barriers to other cities and/or open-sourcing the concept for cities that want to do it on a smaller scale.

“If this was up and running and we were constantly getting orders, we’d be able to make 500-700 tire barriers a month — that would mean 3-5 training positions committed just to this one product,” said Kizzee. “We’re pretty pleased with that.”

While the pilot is still ongoing, there are plans to secure additional funding and expand to other bike lanes in Memphis. For Oyler, the project is all about finding a new purpose: for our tires, for our streets, and even for people. It’s a great example of what local government and community organizations can do when they partner together and take a risk. Memphis, having deadly streets and being resource-limited, was the perfect place for an out-of-the-box idea to flourish.

“This idea could have died but, because of the context we’re in, we have to be open to taking new approaches and trying things that are different,” said Oyler. “When you have a credible community partner wanting to be at the table and help realize an idea like this, why not say ‘yes’ and make it happen?”

Related Topics: