Parking Reform is Key to Building Bike-Friendly Cities

By: Kiran Herbert, PeopleForBikes’ content manager

In order to build safe, convenient bike networks, we need to rethink how we allocate public space and specifically, how we prioritize parking.

In 2008, Tony Jordan’s car broke down and he decided not to replace it. Despite being parents to a two-year-old, Jordan and his wife adjusted to a car-free lifestyle in their Portland, Oregon, home, using Zipcar when they needed it but mostly relying on bikes, transit and their own two feet. A few years later, when he came across “The High Cost of Free Parking,” an 800-page book by Donald C. Shoup, Jordan was already primed to buy it and read the whole thing.

“The book really breaks down why we have parking requirements, how they're based on bogus science, how much it costs and what the impact on housing is,” said Jordan, who was working at the time as a software engineer. “As someone who had a car until not too far before and then read this book — it was something I had never thought about deeply.”

Few U.S. residents think that deeply about parking, other than to complain when we can’t find a spot. For those who own a car, parking can seem like an American right — an ever-present storage space, built free of charge, in the streets in front of our homes or when we drive anywhere in town. When it comes to other personal items, however, we don’t feel like our municipalities are obligated to help us store them. So what makes cars any different?

For one, our cities have long been designed around cars, making their use all but an inevitability except for in the few cities that boast robust transit systems, good sidewalks and complete bike networks. Most places in the U.S. also have had parking requirements — ratios of how many parking spaces each building needs to have — since the 1950s, and few people have the time to read a textbook on the topic. When Jordan finished “The High Cost of Free Parking,” he was able to finally make the connection between parking mandates and other objectively negative facets of modern American society.

“Free parking has had a big impact on a lot of the things — from climate change to housing costs — that aren’t going well,” said Jordan. “I found myself asking, ‘Why doesn’t anyone know this?’”

Jordan, who has a degree in politics and a background in organizing, began looking into Portland’s parking policy and was pleasantly surprised to find the city had begun eliminating parking requirements on certain corridors. However, when a handful of residents spoke up against the move, the mandates were eventually reinstated in 2013. That loss only drove Jordan to do more organizing and coalition-building around the issue.

In time, as things in Portland started to improve, Jordan set his sights on a national effort to help disseminate learnings and scale parking reform efforts across the country. The Parking Reform Network (PRN) quietly launched in March 2020 and has grown organically since. This year, PRN debuted a Mandates Map, which tracks parking reform initiatives throughout the U.S. and Canada. The group also operates a weekly newsletter, which culls parking-related headlines from across the internet, highlighting case studies, pertinent webinars and timely bills.

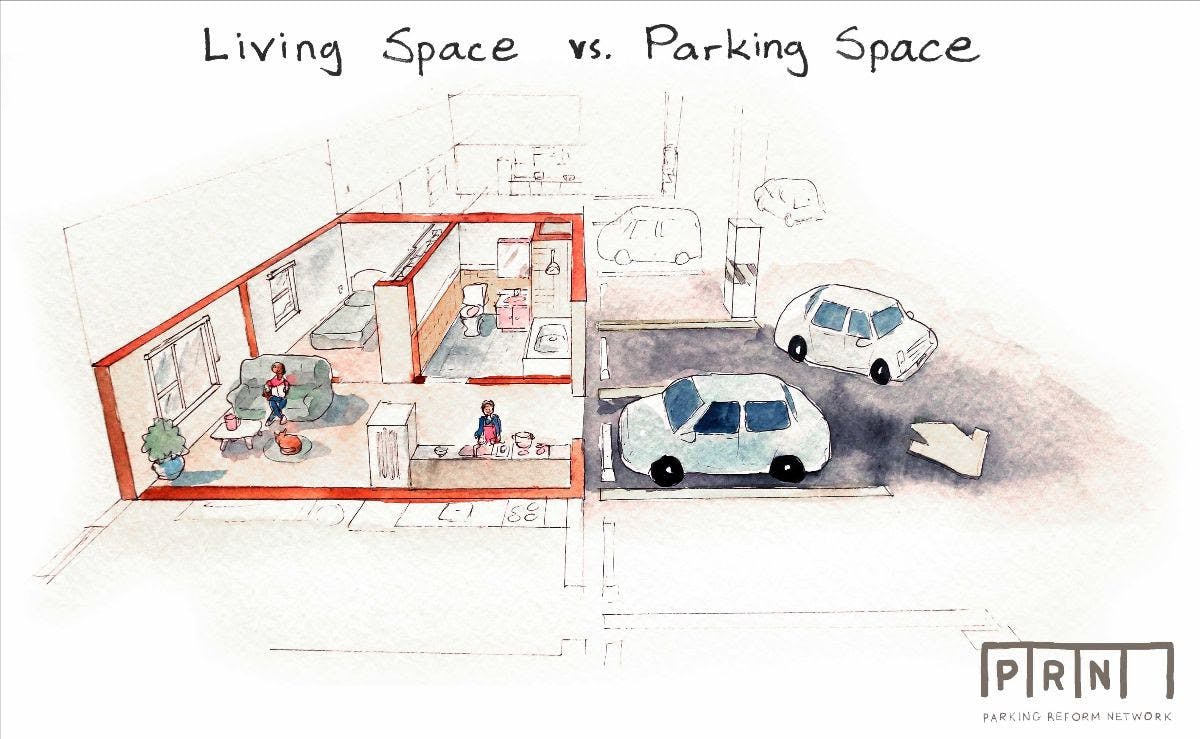

As this Parking Reform Network illustration shows, parking directly affects how much housing we can build.

Reading that newsletter, it becomes clear that parking reform is something that cities big and small are increasingly taking action on, from Sand Point, ID (pop. 8,692) to Ann Arbor, MI (pop. 121,093) to San Jose, CA (pop. 1.029 million). For Catie Gould, a climate and transportation researcher at the Sightline Institute, the growing groundswell of support to reform parking mandates isn’t surprising. “There’s a pretty broad consensus that parking minimums have been a disaster — one of the worst decisions made in North America,” said Gould. “And we’re just now starting to undo the damage.”

As Gould frequently touches on in her writing, required parking takes away from the buildable area of any given site, often resulting in fewer homes and less space for the playgrounds, gardens and walking paths that make communities more livable. Parking is also expensive for new developers to build — it can cost between $40,000 and $60,000 per parking space — which can increase residential housing costs for everyone and take valuable space away from the developable envelope of entitlement space.

What’s more, fewer homes have led to a slew of other intersecting issues: a nationwide housing shortage, an increase in home prices and growing inequity. Lower-income families who drive less and use transit more inevitably end up paying for infrastructure they don’t need while drivers are subsidized for their car use.

When parking is required, buildings are forced to spread further and further apart, decreasing an area’s walkability and leading to urban sprawl, which swallows more and more land to sustain the same population. This in turn pushes people to drive more, upping greenhouse gas emissions, while the ensuing traffic makes it harder for everyone to get where they need to go. Bigger impenetrable areas, like parking lots made of asphalt or concrete, likewise amplify the effects of urban heat islands, making a bad situation worse.

“Today, in most cities, it’s illegal to build downtowns in the way that we associate with them, with lots of buildings being close together,” said Gould, noting that these are often the places you bring visitors and that add to the charm of any destination. “Those places are now in non-compliance with the current code and that code is why our suburbs look the way they do.”

We also don’t need any more parking: By some estimates, there are as many as 2 billion parking spots in the U.S., meaning that there are eight parking spaces for every car. To continue mandating parking just doesn’t make sense.

“All of the best data out there shows that parking is a terrible investment for a city,” said John Bauters, the mayor of Emeryville, California, a small Bay Area city that made the decision to institute widespread reforms. “For us, it made a lot of sense to not have some conscripted amount of parking be required, but instead to give developers, and housing developers in particular, the freedom to design and build something at a more affordable cost that provides a net social benefit to the community and does not further exacerbate our cost of living housing costs and climate issues.”

A better investment, in the eyes of Bauters and many transportation advocates, is a network of protected bike lanes and multi-use paths. His strategy in Emeryville has been to eliminate street parking, immediately turn it into active space and then show how much people use it. Less parking means more proximity — since most people only want to bike one or two miles, the more destinations you have in that radius, the better a place becomes for bicycling. That’s only possible, however, if you’re not required to build big parking lots.

“The problem is we have deprived people for a very long time of any meaningful alternative or choice,” said Bauters. “The reason people expect to move in their cars is that everything has been built for a car. If you want to get people out of a car — whether that be mass transit, walking, biking, scooting, skating, blading, whatever that is — you have to give people a healthy alternative.”

Bauters has seen firsthand how fast people are to adapt their transportation movements, mostly because they have no choice but to figure out how to get from point A to point B. Changing behaviors, however, starts with cities first changing on-the-ground infrastructure. One of the projects Bauters is most proud of is Doyle Street, which runs parallel to two streets designed for car traffic. With a redesign, southbound traffic and parking were eliminated on Doyle Street, essentially transforming it into a pedestrian and bike-friendly zone.

A shot of Doyle Street in Emeryville, California, where a pandemic quick-build was made permanent.

“You don’t have to close the whole street to get cars off of it, you just have to make it undesirable,” said Bauters, adding that in time, the street has become a place for safe movement with virtually no traffic. “We’re changing behaviors.”

Emeryville also launched its own demand-based paid parking program to curb driving. When it comes to prospective development, builders are always shown the city’s robust active transportation plan and, as part of their mitigation efforts, are required to pay into it or pay to build something that supports it. Other times, say if a developer needs more parking in order to obtain financing for a project, Bauters might allow them to add a second story to their parking structure but in exchange, require them to get rid of all the parking on city streets around the project, paying to turn it all into separated bike lanes. In a small city (Emeryville is home to less than 12,000 people), those sorts of negotiations are made easier but that’s not to say they couldn’t be done on a larger scale.

“People buy into the vision because they actually find that their businesses and employees like it,” said Bauters.

In 2020, Seattle was the fastest-growing city in the U.S., with more than 740,000 people. In 2017, Seattle waived or halved off-street parking mandates for new housing near transit, which in turn led to more housing being built and more people moving in. More people in a smaller area leads to more businesses and money being spent, a reinforcing cycle. The revision also contributed to big changes in travel to downtown Seattle: Between 2000 and 2016, transit, walking, biking and rideshare jumped from 50% to 70% of all trips taken in the city. During that same time, drive-alone trips decreased from 50% to 30%.

There are many great examples of what less parking might mean for a city and bicycling — just look to Paris or Amsterdam, places where leadership understands that the only way to increase space for bikes is to decrease space for cars. Recently, the Filipino capital of Manila introduced a bill requiring car owners to show proof they have off-street parking before registering their vehicle, a move that hopes to mimic the success of nearby Japan’s proof-of-parking law, which all but bans on-street parking.

In the U.S., more and more cities continue to eliminate their parking requirements each week, and the issue has been making national headlines, thanks to a recent bill in California (AB-2097) that would reform parking mandates near public transit statewide. Rep. Earl Blumenauer of Oregon also recently introduced Parking Cash Out Legislation, which would require employers to offer a parking cash out option to employees who are otherwise offered a parking benefit.

Getting people passionate about parking, however, is difficult, especially when driving is the easiest way of getting around and parking remains free and abundant. It’s a politically ripe topic and people tend to have a lot of very strong feelings, especially when it comes to parking on their neighborhood block. As a politician, Bauters is on the receiving end of a lot of folks’ opinions on parking — his strategy is to relate to people in the way they’re relating to him: with emotion.

“I don't ask them to get out of the car, I don't tell them they're burning the planet, I don't tell them that they're a risk to everybody who's in a crosswalk — I don't blame them for anything,” said Bauters. “But what I don't do is I don't apologize for prioritizing everybody's well-being, not just theirs.”

It’s in the best interest of the collective good to start doing things differently, and that requires bold action when it comes to eliminating parking mandates and building the sorts of connected bicycle- and pedestrian-friendly networks that offer people safe, convenient alternatives to driving.

“If you can only move in a car, people don't imagine or believe that they can do anything else,” said Bauters. “You have to take space back to give people the chance to do that safely — and the first thing that should go is always parking.”

Related Topics: