Virginia’s Fastest-Growing County Makes Room for Bicycles

By: Emily Furia

fficially, Loudoun County’s motto, “I byde my time,” comes from the family coat of arms of John Campbell, the fourth Earl of Loudoun and a commander of British forces in North America. Until recently, it was also a fitting description of the region’s approach to bike infrastructure.

The county — which includes Dulles International Airport, portions of the western suburbs of Washington, D.C., and miles of scenic horse and wine country — hasn’t typically made bike infrastructure a priority, especially compared with urban sections of the DC metro area. But since striping its first bike lanes in Leesburg in 2015, Virginia’s fastest-growing county has steadily expanded its bicycle network. And as two recently approved bike projects come to fruition, the county stands to welcome large numbers of both touring and commuting bicyclists.

A dream come true

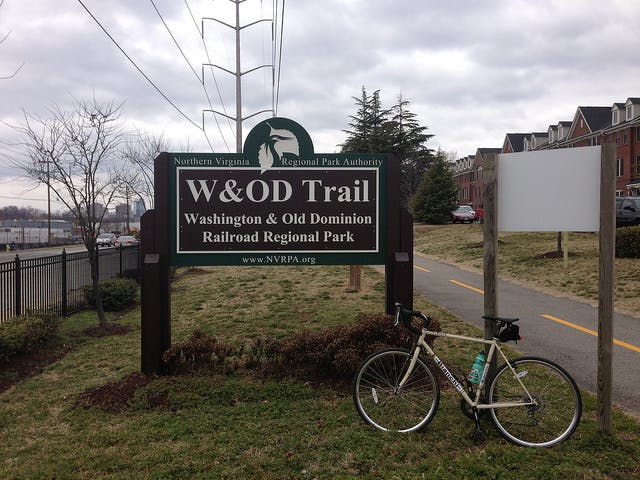

The new bikes lanes in Leesburg “primed the pump” to encourage local officials to tackle other projects, says Dennis Kruse, president of the advocacy group Bike Loudoun. The organization worked with the town to create eight miles of shared-use paths that connect to the Washington & Old Dominion Trail, one of the region’s most popular rail trails.

The W&OD Trail extends for 45 paved miles from the Shirlington neighborhood in Arlington to the town of Purcellville in western Loudoun County. In Leesburg, the trail attracts both retailers and residents. Donald Knutson, one of the builders behind Crescent Place, a mixed-use development that opened in 2016, credits part of the complex’s success to its location just blocks from the trail; he’s currently developing another site that will include a trailside seating area.

Leesburg has the opportunity to capitalize on the trail even further: The regional transportation board recently approved a project to widen State Route 15, which connects Leesburg to Poolesville. The town is home to White’s Ferry service and is one of the few places where bicyclists can cross the Potomac into Maryland — and catch the Chesapeake & Ohio Towpath, an old canal trail that hugs the border of Maryland and links to Washington, D.C. The widening plans include an off-street path, which will not only make the approximately four-mile ride from Leesburg to White’s Ferry much safer, but also create a car-free loop between Washington and Leesburg by connecting the W&OD Trail with the C&O Towpath.

Local cyclists “have had this dream of connecting the two trails,” says Kruse. Touring bicyclists already ride this route, often taking advantage of the shuttle service several Leesburg hotels offer from the ferry. But by providing safe bike access into town, “we’ll have significantly more loop traffic,” Kruse says. The town will also be better equipped to welcome through riders making the 300-plus mile trip from Pittsburgh to Washington, D.C., on the Great Allegheny Passage and C&O paths. Kruse says the design process for the connector trail is in progress; the project could be finished as early as 2021.

Prepping for Metro

Once primarily a recreational trail, the W&OD now attracts bike commuters year-round. (Authorities have taken notice: Last winter the Northern Virginia Regional Parks Authority announced it would begin pre-treating the trail when snow is in the forecast, in addition to plowing after a storm hits.)

The trail stands to become even more popular with commuting bicyclists in 2020, when three new Metro stations will open in the county as part of the Silver Line extension. (Also moving in that year: The U.S. Customs and Border Protection Agency’s Office of Information Technology, which recently announced its plan to relocate its headquarters.) In anticipation of the influx of commuters, Bike Loudoun is working to help the county close gaps in the area’s bike network and create signed, safe routes for bicyclists and pedestrians from the W&OD to the stations.

Funding for the project was recently approved, Kruse says, in hopes of attracting another major employer: Amazon. Loudoun and Fairfax Counties submitted a joint bid to land the online retailing giant’s second North American headquarters, and made the list of 20 finalists released earlier this year. Amazon’s request for proposal asks about bicycle access (20 percent of its employees at its Seattle headquarters use non-motorized transportation to get to work, according to the New York Times), which helped convince the county to step up its infrastructure, Kruse says. No matter how the competition plays out, it’s a win for people on bikes — and everyone else, who will enjoy fewer traffic jams and cleaner air.

Loudoun County’s journey toward bike friendliness isn’t complete, and it hasn’t been easy. With the advent of the Metro stations, “We’re now trying to tackle urban, suburban and rural environments, says Kruse. “Most areas only have to deal with one of those. But we’re making good headway.” While the county may have traditionally lagged behind its more densely populated counterparts when it comes to welcoming bikes, it picked a great time to get started.