L.A. Researchers Hope to Make ‘Bikepooling’ a Thing

By: Kiran Herbert, PeopleForBikes' local programs writer

A $1 million National Science Foundation grantee aims to bring safety in numbers to underserved bike commuters, creating communal art in the process.

Fabian Wagmister, an Argentinian-born artist and associate professor at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), didn’t consider himself much of a bicyclist until he turned 50. It was then that his wife, in an attempt to facilitate a healthier lifestyle, bought him a bike. Within a week, he’d decided to ride the 15 miles from his downtown home to the UCLA campus. That journey transformed the way he saw L.A., igniting a passion for traveling on two wheels.

“The bicycle has been largely a rebirth for my body and my sensibilities towards the city,” said Wagmister, whose physical and emotional health has since improved. “I get on the bike and recover that sense of childhood to a degree. It’s made me a more playful, relaxed human being.”

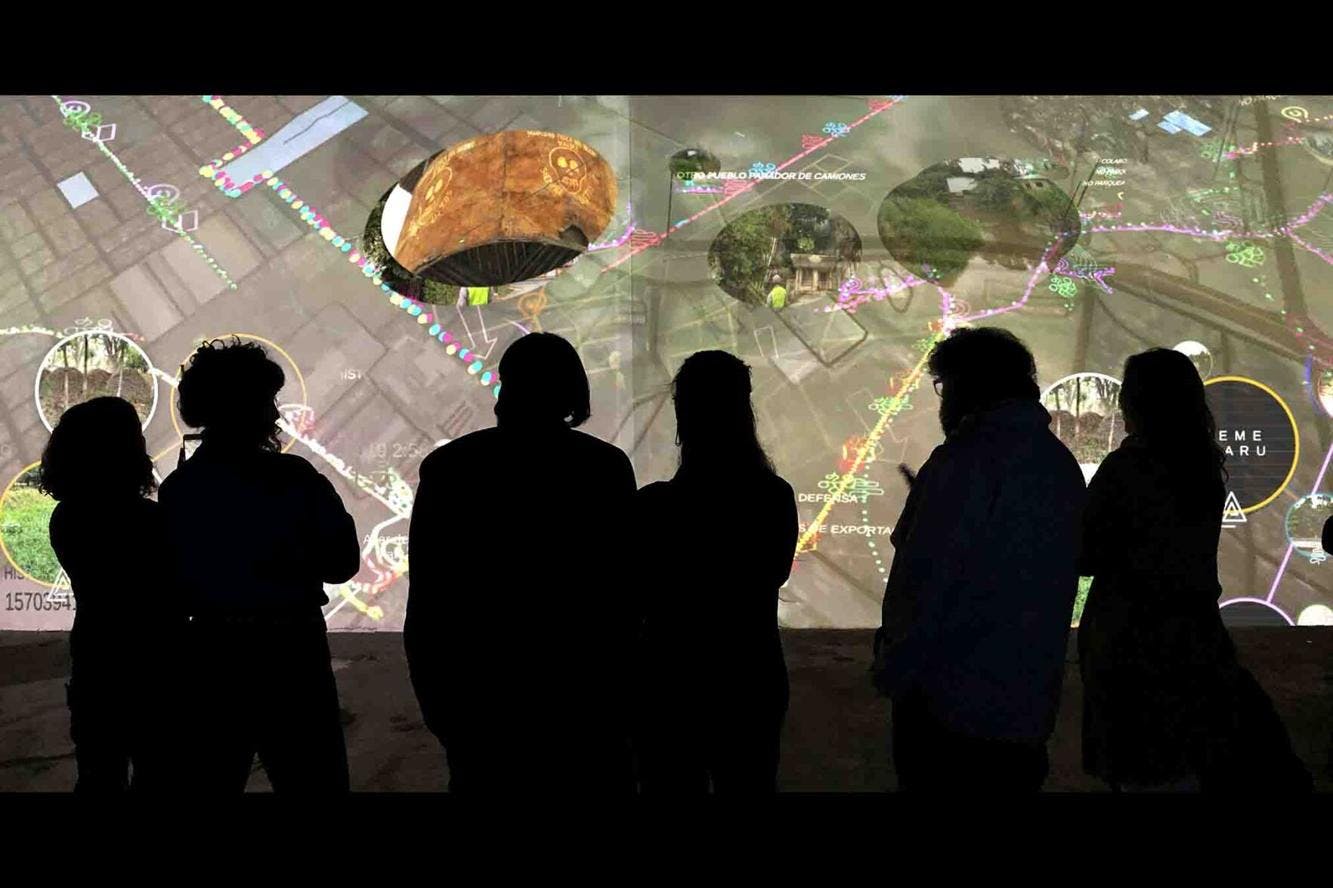

Wagmister became a bike person and, in classic fashion, he soon wanted to convert others. In addition to bike commuting, he started taking his kids to school by bike and planning long bike tours. The bicycle became a tool for discovery and self-exploration, which led to Wagmister’s evolution as an artist. One 2017 project, “Bicicletas Blancas,” took place over six nights in Buenos Aires. From sunset to sunrise, Wagmister — decked out with sensors that measured things like location, heart rate, pedaling cadence and vibration, as well as microphones that captured sound — explored the city and his own emotions. As he biked, the data from each ride was processed algorithmically to control a light sculpture and interactive map.

“Everything I was experiencing was being transmitted live to an installation in an art gallery,” said Wagmister, who has a particular interest in combining technology and art in community-forward projects. The rides attracted other bikers and passersby, sparking connections and inspiring Wagmister to gift a bike to a stranger each night. “That is who I am — that’s the kind of art that I do and that I enjoy.”

In the years since, Wagmister has continued to create technology-based bike art, always inviting everyday riders to participate. He’s also taught other artists to design these types of artworks, cultivating a collective of bicycle artists that span the globe from Costa Rica to Switzerland. When the National Science Foundation (NSF) announced its Civic Innovation Challenge in 2021, Wagmister began dreaming up a new project that would focus on underserved communities in L.A., this time using art as a way to facilitate ‘bikepooling’ (like carpooling but for bike commuters).

The Civic Innovation Challenge sought ready-to-implement projects that would offer better mobility options for neighborhoods that suffer from spatial mismatch, or inconsistency between low-income households and suitable job opportunities. Knowing that any mobility research project administered by an art professor would be a longshot, Wagmister recruited his friend and colleague, Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, Ph.D., an associate dean and well-respected professor of urban planning. For more than three decades, Loukaitou-Sideris has focused her work on city public spaces, examining how we might better design our parks and green spaces for people that have been neglected due to their race, gender, age, income and/or housing status.

“When I was asked to participate, I was really excited,” said Loukaitou-Sideris. “We’re trying to make bicycling accessible to communities that have typically been marginalized in terms of mobility.”

In February 2021, Wagmister, Loukaitou-Sideris and Jeffrey Burke, an associate dean of research and technology at UCLA, secured an initial $50,000 NSF research grant. The team used the funding to partner with the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition and trusted community-based organizations in downtown L.A., including Los Angeles River State Park Partners and the Anahuak Youth Sports Association, which primarily serve historically-marginalized Latino and Chinese neighborhoods. Wagmister, by nature of where he lives in L.A. and his earlier art projects, already had deep ties to the area. Together, the team distributed and analyzed more than 700 surveys to better understand residents’ mobility habits and needs.

From that initial research phase, the Civic Bicycle Commuting (CiBiC) project began to take shape: The team would develop a user-friendly app that allows local commuters to join ‘bike-to-work flows,’ creating a safety-in-numbers effect as they chart routes across L.A., which would then be digitally translated into public art pieces. The same nonprofits that helped with the initial outreach would be tapped to support the project by subcontracting additional organizations, recruiting riders and disseminating more surveys. In September 2021, the NSF found the project compelling enough to grant the team the final $1 million round of funding.

While still in the development stage, the pilot project will run for about a year and target the low-income communities surveyed in the research phase, among whom car ownership is low. Since downtown L.A. is lacking in bicycle infrastructure (its Bicycle Network Analysis score is just 26/100) and suffers from many of the same perceptions of bicyclists that we see nationally (namely, that they’re wealthy, white and male), CiBiC is an attempt to rethink urban bicycle commuting. By using technology to connect people — helping them identify and join bike flows — the hope is to promote a feeling of safety, motivation and camaraderie, turning a once dreaded commute into something healthy, sustainable and economically viable.

“Inclusion is a main driver of the project,” said Wagmister. “Part of what we want to do is transform L.A. bike culture from being a male, 20 to 30-year-old activity to being a communitywide activity. Our target rider would be a 45-year-old mother that has never taken her bike to her work — we want to make bike riding a possibility for those who have never considered it.”

In order to ensure novice riders feel comfortable, researchers plan to continue collaborating with the local community bicycling organizations, incorporating an educational component as well as recruiting experienced bikers to lead the bikepools. In addition to compensating the leaders, the plan is to also offer different financial incentives to encourage people to start bicycling. For those without access to a bike, donations and bike share are all on the table as possible options (METRO, the transportation agency that oversees L.A.’s bike share system, is an important partner on the project and already offers reduced-fare bike share passes for those in need).

Many of the people in the target area have a commute between 1 and 5 miles, ideal for biking, and the plan is to design certain bike corridors that meet the group’s needs. For individuals with longer commutes, the hope is that the presence of bike flows will make it easier for people to connect biking with other modes of transit, like biking to a subway station. In a culture where commuting is generally considered a solo endeavor, CiBiC will ask people to come together to ensure one another’s safety as a group, sacrificing a little efficiency for comfort and creating a vibrant bike community in the process.

“For women, the issue of sexual harassment in public transit environments is very real,” said Loukaitou-Sideris, noting that alongside infrastructure, it’s one of the main reasons women don’t participate in biking. “A group of people biking together will make people feel less scared of being harassed and run over by traffic.”

While a mass of bicyclists taking over city streets might seem like a far-fetched Utopian dream, the idea of riders achieving safety in numbers — often dubbed critical mass — isn’t a new concept. In fact, the L.A. Critical Mass ride, which takes place on the last Friday of every month, is known as “America’s largest community bicycle ride.” In the last year, more and more families have turned to group bike commutes to make kids’ journeys to school safer. Known as a ‘bike bus’ or ‘bike train,’ such events have gained notoriety in cities like San Francisco and Barcelona, effectively shutting down streets to cars. Who’s to say a group of adult commuters couldn’t do the same? The researchers plan on prototyping a few flow corridors to start but hope to eventually have hundreds of routes across the city.

For Wagmister, the social technological component, as well as the collective creation of art, is key to rallying folks around the cause and generating a feeling of ownership.

“In the CiBiC system, bicycling is about going to work but it’s also a creative cultural activity,” said Wagmister, explaining that by projecting the routes in a public art display, people will be allowed to interact with the commuters in real-time. Information will be taken from the app, which will also have a journal component where people can share written and video feedback of their journey. “By riding in our system, you’re part of a collective of authors creating this amazing artwork.”

Of course, the CiBiC project is still research, and the team can’t say for sure how participants are going to feel afterward. Wagmister secured additional funding to run a simultaneous pilot in Buenos Aires, where the culture is different and the bike infrastructure is better. Still, he’s optimistic that both experiments will result in an increase in the quality of life for participants. If successful, the hope is that Metro will be able to maintain CiBiC long-term, positioning L.A. as an innovative mobility leader when it comes to meeting sustainability and equity goals.

“The concept of human infrastructure driven by people in terms of the needs of people — it’s about time we start thinking about our communities that way,” said Wagmister. “Let’s let our communities design the way they want to go to work and then we can provide the support based on what they tell us they need.”

Related Topics: