Bike and Transit Together Tackle Cars

By: Michael Andersen, PlacesForBikes staff writer

If you’re not putting transit connections at the heart of your bike planning, you’re not doing it right.

If you’re not building transit streets and stations that make biking to transit attractive and intuitive, you’re not building them right, either.

Those were two implications from a remarkable keynote address delivered to our crew of study tour delegates Thursday by Marco te Brömmelstroet, academic director of the Urban Cycling Institute at the University of Amsterdam.

Te Brömmelstroet built his talk around a trio of bike-planning myths that he wanted to bust. Or, at least, myths he wanted to make more complicated. Here was the second of the three:

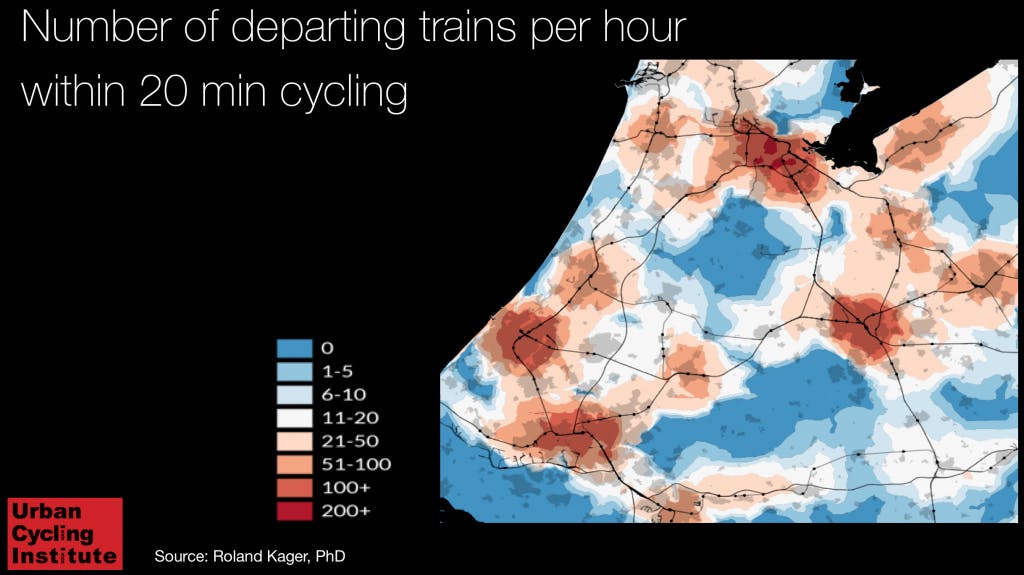

Most American planners generally understand that biking makes it easier for more people to reach a high-quality transit station. But in the chart below, te Brömmelstroet showed in an unusually analytical way how this combination compares to other options:

Transportation modes that are higher on the chart move more quickly; modes that are further right bring people to destinations more directly.

In transportation planning jargon, this is the difference between mobility and access.

“That is why driving is popular,” te Brömmelstroet said. “It offers door-to-door accessibility and high speeds.”

Driving is also expensive, of course, if you include the costs of car ownership. And as the chart shows, there’s also a big difference in speed between uncongested and congested roads. That’s the unavoidable problem, of course: When more people drive, driving becomes less efficient.

Mass transit is just the opposite. When more people ride a bus or train, the buses and trains become more efficient. And if moving around the Netherlands demonstrates anything, it’s that a comfortable, direct and intuitive biking network makes it much, much easier to get around on transit.

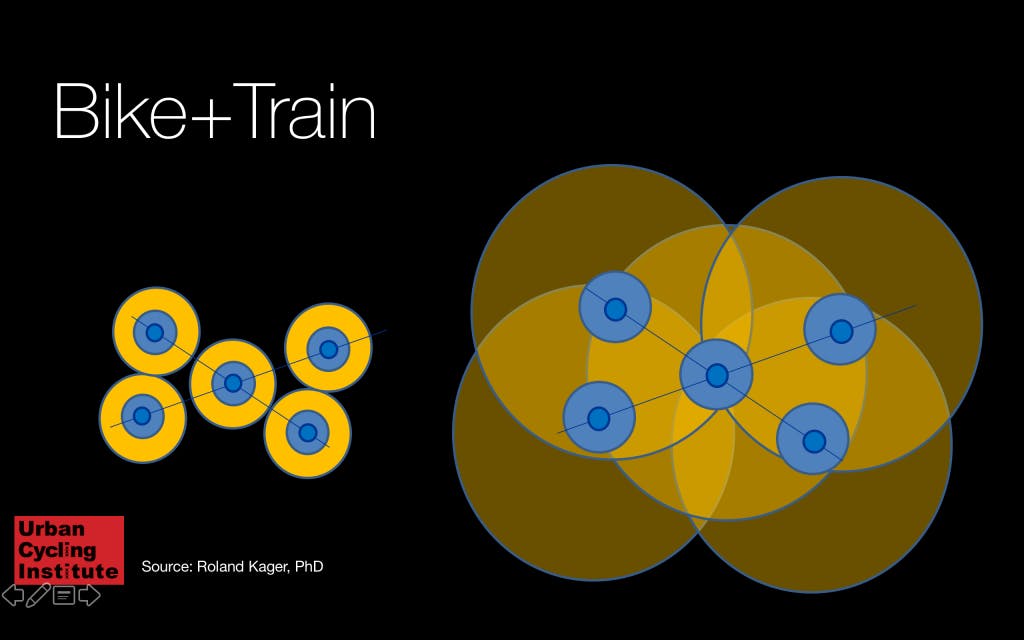

Te Brömmelstroet has an image for that, too. The circles to the right represent the distance people will travel to reach a train station by foot (in blue) or by bike (in yellow).

According to te Brömmelstroet’s calculations, just over 80 percent of the Dutch population lives in one of the yellow areas, able to bike no more than 4.7 miles (7.5 kilometers) to a commuter rail station.

But even more importantly, he said, most Dutch people live in one of the lighter yellow areas. The average Dutch person lives within the catchment area of 3.5 different rail stations.

That means Dutch people have more than access. They have the most valuable transportation commodity of all: choice.

“If you combine the bike and the train — if you can choose and mix — you get a very flexible choice,” te Brömmelstroet said. “I can choose exactly the moment when I will need 140 km per hour speed.”

Together, biking and transit create a new mode that beats cars on speed, at least in urban areas, and nearly beats them on directness. And, of course, the combination far exceeds biking or transit alone.

“I’m outperforming the two systems,” he said. “It’s a synergistic new system that emerges.”

Discussing te Brömmelstroet’s ideas during our final tour session on Friday, the delegation from Austin coined a half-joking term for this new value they were now planning to build into their transportation network: “multinodality.”

Mike Trimble, director of Austin’s huge new corridor construction program, which expects to add 40 miles of bike lanes to major streets in the next seven years, said te Brömmelstroet’s ideas echoes opinions already expressed by Austinites in public polls.

“People want to have a choice to bike; they want to have a choice to use transit,” he said. “We’ve already heard that. … I think the more we show that it’s a logical connection between the modes at the nodes, then people are going to have better options to move around the city.”

Related Topics: